Digital Doubles in Hollywood: The Future of Acting?

- Mimic Productions

- Dec 30, 2025

- 12 min read

The idea that an actor’s performance can be extended, duplicated, or even resurrected through pixels is no longer speculative fiction. It is an everyday production reality. Digital doubles in film and high-end CGI actors sit at the intersection of performance, engineering, and ethics, reshaping how directors block scenes, how stunt coordinators plan risk, and how actors negotiate their contracts.

Handled well, these virtual stand-ins are not shortcuts. They are precision tools: photoreal replicas built through scanning, rigging, motion capture, and careful supervision so that every digital frame still belongs to a human performance. Handled badly, they threaten trust, authorship, and the audience’s ability to believe what they’re seeing.

This article looks at how digital replicas actually work inside the pipeline, where they make sense creatively and practically, and whether they represent an existential threat to acting or simply the next evolution of screen performance, informed by film-grade digital human practice.

Table of Contents

Core Sections

1. What Are Digital Doubles and CGI Actors?

In contemporary VFX, a digital double is a high-fidelity 3D replica of a specific performer, built to be indistinguishable from the original on camera. It inherits the actor’s proportions, likeness, facial nuance, and even pore-level detail, and is typically driven by captured performance data from that same actor.

This is different from a generic CG character. A fully invented creature or stylized character might be animated from scratch or driven by a different performer. A digital stunt double, by contrast, is anchored to a single on-screen identity: it exists so the audience believes they are still watching the same person, even when the shot would be impossible or unsafe to capture practically.

When people talk about CGI actors, they can mean two things:

A digital stand-in for a real performer (a digi-double or stunt double).

A virtual actor: a character with no real-world counterpart, often driven by motion capture and facial capture, sometimes combined with AI-assisted animation.

If you want a more cinematic overview of how these technologies are changing storytelling, the broader evolution is explored in Mimic’s article on the journey from Hollywood blockbusters to AI-driven avatars, which traces how digital humans moved from background effects to central performances. Mimic Productions You can see that story arc expanded in this look at the evolution of digital humans from Hollywood to AI avatars.

2. Inside the Digital Double Pipeline

Regardless of the studio, the process of building a digital replica follows a similar high-level sequence. The terminology may change, but the logic does not.

2.1 Capture and Scanning

It starts with the actor.

Most productions commission a 3D scan of the performer on a dedicated capture stage. Photogrammetry or structured-light systems capture the actor from all angles, producing geometry and texture maps with millimetre-level precision. This is often accompanied by a separate facial capture session, collecting neutral and extreme expressions to inform the facial rig.

This is where intent is set. The contract and creative brief determine whether the digital asset will be used for stunts, crowd extensions, de-aging, or potential reuse across sequels.

2.2 Topology and Character Modeling

Raw scan data is not animation-ready. Modelers rebuild the actor’s head and body with clean, animation-friendly topology, preserving the scan’s detail while ensuring the mesh deforms correctly.

At this stage, artists also craft different variants: wardrobe changes, injury versions, or digital prosthetics (for instance, a more muscular hero version for wide shots). High-resolution displacement maps capture skin microstructure, wrinkles, and pores so that close-ups hold up under cinematic lighting.

2.3 Rigging and Facial Systems

Rigging is the mechanical engineering of the digital human.

A body rig defines how the skeleton moves; a facial rig defines how expressions, phonemes, and micro-movements are driven. Depending on the production, the team may:

Use FACS-based facial rigs for granular expression control.

Implement blendshape systems and correctives for subtle skin behavior.

Add muscle, tendon, and fat simulations for realistic secondary motion.

For a deeper dive into how these skeletal and facial systems are constructed, Mimic’s breakdown of character rigging and deformation workflows explains why a robust rig is non-negotiable for believable digital humans.

2.4 Motion Capture and Performance Capture

Once the asset is ready, the question becomes: who drives it?

For many productions, the answer is still the original actor. Full-body motion capture and dedicated facial capture allow performers to deliver a continuous, emotionally coherent performance that can later be transferred to their digital replica.

In stunt-heavy sequences, a specialist may take over. The production might:

Capture a stunt performer in a mocap volume for high-risk action.

Use performance capture for close-quarters, emotional beats.

Combine on-set witness cameras with mocap data for complex shots.

If you want to understand the nuance between capturing a body in motion and capturing a full acting performance, Mimic’s analysis of motion capture vs performance capture is a useful reference for how different productions choose their tools.

2.5 Shading, Lighting, Simulation, and Render

With performance in place, the digital double passes into the lighting and rendering pipeline:

Shading teams create physically based materials for skin, eyes, hair, and cloth.

Groom artists build hair and fur systems, critical for both likeness and silhouette.

Simulation teams handle cloth, muscles, and any dynamic FX interaction.

Lookdev and lighting ensure the digital stand-in matches the plate photography—lens distortion, grain, even on-set imperfections.

In high-end work, rendering may be split between offline path tracing for hero shots and real-time engines for virtual production or interactive previews. Real-time and pre-rendered workflows each have their place; Mimic’s comparison of real-time rendering and pre-rendered pipelines outlines where each approach is strongest in a film context.

3. Why Productions Choose Digital Replicas

Digital doubles in film are not used because directors don’t want actors on set. They are used because some shots are unsafe, impractical, or physically impossible to capture with a human body in frame.

Common reasons:

Safety and stunt amplificationComplex explosions, high falls, or near-miss vehicle impacts can be simulated with a digital body, while the actor’s close-up performance is shot practically.

De-aging and time manipulationDe-aged performances combine current-day acting with younger digital likenesses, allowing characters to span decades within one film.

Reshoots without full cast returnsTight deadlines or unavailable actors can be bridged with digital stand-ins, especially for wide shots or short inserts.

Crowd replication and background workA few scanned extras can become hundreds of unique-looking background performers, freeing production from massive crowd logistics.

Physical limitationsSome choreography, creature transformations, or zero-gravity sequences simply cannot be achieved with a human body without heavy compromise.

A detailed real-world breakdown of how filmmakers are already using these tools can be found in Mimic’s own exploration of digital doubles in cinema and how AI-driven avatars are changing filmmaking.

4. Digital Doubles vs Fully Synthetic Performers

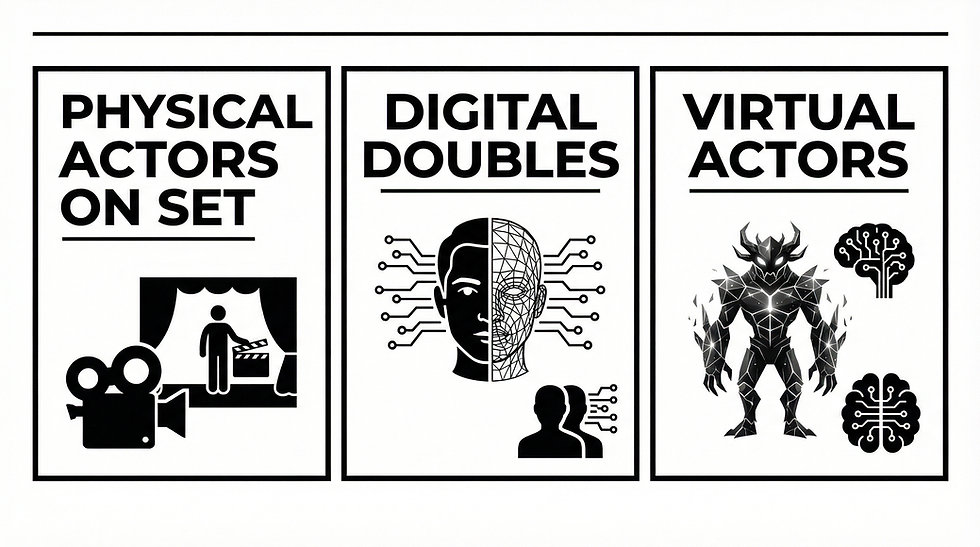

It’s useful to separate three categories:

Physical actors on set – captured entirely in-camera.

Digital doubles – 3D replicas tied to a specific performer.

Virtual actors – characters that exist only as digital entities, without a real-world counterpart.

Digital doubles carry the identity and legal framework of the original performer. Their likeness is licensed; their performance is usually authored by that actor or a contracted double.

Virtual actors—what many people loosely call CGI actors—are different. They might be driven by an actor’s motion, but they are not trying to mimic a known human. They may be humanoid, stylized, or entirely creature-like. In some experimental workflows, AI-driven animation layers are added atop captured motion, but even then, high-end productions rely on supervisors to control every frame for continuity and intent.

This distinction matters for both contracts and audience perception. When viewers feel that a real person’s likeness has been replicated without consent, the reaction is very different than when they meet a purely fictional virtual character.

5. Ethics, Consent, and Ownership

Digital replicas raise hard questions that go beyond rendering and shading.

Key issues include:

Informed consent: Does the performer fully understand how their digital likeness can be used—now and in future productions? Are there explicit limits (e.g., no new dialogue after death, no recontextualization in different genres)?

Posthumous performances: Recreating deceased actors has proven emotionally and ethically complex. Even with estate approval, there is an ongoing debate over whether audiences are fully comfortable with seeing new scenes from someone who can no longer speak for themselves.

Actor unions and residuals: Guilds are pushing for clear rules on when a digital double is considered a reuse of existing material versus a new performance requiring compensation.

Deepfakes vs professional digital humans: Cheap, unauthorized neural-face replacements have sharpened the distinction between serious digital human work and synthetic manipulation done without consent. Mimic’s guide to the difference between deepfakes and crafted digital humans explores how trained eyes can spot the tell-tale artifacts and what ethical frameworks responsible studios follow.

Ultimately, the future of digital doubles hinges less on technology and more on trust. When performers know exactly where the boundaries lie, they are much more willing to experiment with digital counterparts.

Comparison Table

Physical Actors, Stunt Doubles, Digital Doubles, Virtual Actors

Aspect | On-Set Actor (Practical) | Practical Stunt Double | Digital Double (Actor-Linked) | Fully Virtual Actor / CG Character |

Basis | Real performer | Real stunt performer | 3D replica of a specific performer | Entirely designed character |

Safety | Limited by human risk | High risk, but still physical | Safest for extreme or impossible shots | Safest; exists only digitally |

Likeness | Original actor | Resembles actor with makeup/costume | Photoreal, indistinguishable when done well | No obligation to match any real person |

Performance Source | Live action on set | Live action stunts | Motion capture, facial capture, animation blending | Mocap, keyframe animation, procedural or AI-driven |

Best Use Cases | Dialogue, nuanced acting, close-ups | High-intensity stunts | De-aging, dangerous stunts, impossible camera moves, reshoots | Creatures, stylized worlds, non-human or invented roles |

Cost Profile | Day rate + overhead | Stunt premiums + insurance | High upfront build cost, scalable reuse across shots and sequels | High design and build cost, reusable character asset |

Ethical Complexity | Standard performance contracts | Standard stunt and safety regulations | Requires clear likeness rights, future-use clauses | Mostly IP and creative ownership questions |

Creative Flexibility | Constrained by physical set and schedule | Constrained by what’s safe and practical | Extreme camera freedom, timing control, repeatability | Unlimited, but must still feel grounded to be believable |

Applications

Digital doubles and advanced CGI performers already support a broad range of production scenarios in Hollywood and beyond.

1. Action and Stunt-Heavy Sequences

High-end action films lean on digital stunt doubles not to sideline stunts, but to extend them. A practical car roll might be captured once, with digital extensions adding debris, secondary impacts, or altered trajectories while keeping the performer recognizable.

2. De-Aging and Time Shifts

From flashbacks to multi-decade sagas, de-aging has become one of the most visible uses of digital replicas. An actor can play their younger self without recasting or extensive prosthetics, keeping emotional continuity while the digital counterpart handles the visible age shift.

3. Body Transformation and Augmentation

When stories demand extreme physique changes—superhuman musculature, altered proportions, or partial cybernetics—digital doubles allow for transformation without unhealthy weight manipulation or full-time prosthetics.

4. Complex Camera Moves and Virtual Production

In virtual production, directors might move cameras through spaces that would be physically impossible for crane or Steadicam. Digital doubles allow actors to “travel” through these moves, blending plate photography, LED stages, and fully synthetic shots without breaking continuity.

Mimic’s discussion of virtual production versus traditional filmmaking outlines how these tools change planning, blocking, and the role of VFX on set.

5. Live Entertainment and Cross-Media Characters

Digital humans don’t stop at features. The same assets can appear in trailers, interactive experiences, XR installations, or even live events as holographic performances. When carefully planned, a single digital double can carry a character across mediums for years.

Benefits

1. Safety Without Sacrificing Spectacle

The most obvious benefit is risk reduction. Dangerous gags can be simulated, not survived. That protects actors, stunt teams, and crew while still delivering a kinetic, visceral experience to the audience.

2. Creative Freedom in the Edit Suite

With a robust digital asset, directors and editors gain temporal and spatial flexibility:

Extend or shorten beats without being limited to the original coverage.

Reframe shots in post, shifting the camera path inside a fully CG environment.

Seamlessly bridge continuity gaps with digital transitions and re-projected performances.

3. Asset Reuse and Franchise Continuity

High-quality digital doubles are expensive to build, but once created, they become part of a studio’s IP. They can be reused across sequels, spin-offs, and marketing materials, preserving visual continuity even as schedules and locations change.

4. Performance Preservation

When captured and archived responsibly, a performer’s nuance—micro-expressions, physical idiosyncrasies, and unique body language—can be preserved as a performance library. That doesn’t mean infinite reuse without consent; it means the craft of a performance can be referenced, studied, and built upon within clear boundaries.

Challenges

1. The Uncanny Valley

Even with cutting-edge scanning and shading, audiences are exquisitely sensitive to human realism. Small errors in eye motion, lip timing, or skin response can break the illusion. Digital doubles must be supervised at a frame-by-frame level to avoid sliding into the uncanny valley.

2. Pipeline Complexity and Cost

Building a film-grade digital human is not trivial. It requires:

Dedicated capture stages and specialized crews.

Skilled modelers, riggers, groom artists, lighting TDs, and compositors.

Render infrastructure and disciplined asset management.

The up-front cost is significant, which is why responsible productions deploy digital doubles where they genuinely add value, not as a default.

3. Legal Frameworks Still Catching Up

Union agreements, national regulations, and studio policies are all evolving. Issues include:

Limits on reuse of scanned likenesses.

Residuals for synthetic performances derived from past work.

Clear labelling of AI-assisted or AI-generated material.

Until standards settle, productions must work closely with legal teams and talent representatives to avoid future disputes.

4. Audience Trust

The more invisible digital actors become, the more the industry must earn trust by being transparent about how and why they are used. Misinformation around deepfakes has made viewers understandably wary; responsible studios differentiate their methods and ethics clearly, as highlighted in Mimic’s coverage of how to distinguish deepfake-style manipulations from crafted digital humans.

Future Outlook: Is This the Future of Acting?

Digital doubles and CGI-driven performers are not replacing actors; they are reshaping the toolkit around them. The most compelling work in the next decade is likely to follow a few trajectories:

Hybrid performances: Actors will increasingly perform both on physical sets and in capture volumes, with their digital counterparts extending action, traversing impossible spaces, or inhabiting stylized worlds.

Real-time digital humans on set: As real-time rendering advances, directors will be able to see final-quality digital doubles inside the camera feed, adjusting blocking and performance in the moment rather than waiting for post.

Actor-owned digital identities: Performers may maintain their own licensed digital selves—portable assets that they can bring into different productions under their control, rather than assets owned solely by a single studio.

Ethical frameworks as a creative feature, not a constraint: Productions that clearly foreground consent, authorship, and fair compensation will have an easier time attracting top talent and aligning with audiences who care how the work is made.

In that sense, the future of acting is not about actors competing with their digital shadows. It is about actors collaborating with them—an expanded practice where physical presence and digital embodiment are both recognized as legitimate forms of performance. Studios like Mimic Productions are already structured around this hybrid reality, combining scanning, rigging, motion capture, and AI-assisted workflows to support both the craft and the performer behind the pixels.

FAQs

1. Will digital doubles replace human actors?

Highly unlikely. Digital replicas are tools for difficult, dangerous, or impossible shots—not full replacements for human presence. The emotional core of a performance still comes from a person, even when extended through a virtual body.

2. How long does it take to create a high-end digital double?

Timelines vary, but a premium, hero-level digital replica can take weeks or months to build, test, and integrate into a production-ready pipeline. Subsequent reuse is faster, which is why franchises invest in building robust character assets.

3. Are actors paid when their digital double is used?

This depends on contracts and union regulations. Increasingly, clauses specify how a scanned likeness can be reused and how compensation is handled when new scenes are generated from captured data rather than fresh on-set work.

4. How is this different from simple CGI or game characters?

Game characters are often designed for real-time environments with different constraints, stylization, or lower per-frame budgets. Film-grade digital doubles aim for photographic realism and must hold up under high-resolution scrutiny, which demands more detailed capture, rigging, and rendering.

5. Is AI actually animating these digital actors?

AI tools can assist—cleaning mocap data, generating in-between motion, or suggesting variations—but high-end film work still relies on human supervisors and animators. The goal is not automation for its own sake; it is controlled, directed performance. For more on where AI fits in, Mimic’s article on AI’s impact on 3D character animation workflows offers a grounded view from production.

Conclusion

Digital doubles and advanced CGI performers are not a gimmick. They are the logical outcome of decades of work in scanning, rigging, motion capture, shading, and rendering—applied to protect performers, expand visual storytelling, and sustain continuity across increasingly ambitious projects.

The future of acting will almost certainly be hybrid. Actors will still stand under hot lights, deliver lines, and rehearse blocking. But they will also step into capture volumes, collaborate with digital supervisors, and lend their craft to characters that live as much in data as in flesh.

The question is not whether digital doubles in film are the future of acting. The question is how the industry chooses to integrate them: with ethical clarity, creative discipline, and respect for the human beings whose performances make every digital frame worth watching.

Contact us For further information and queries, please contact Press Department, Mimic Productions: info@mimicproductions.com

.png)

Comments